Skip to content

As the American middle class nears the endangered species list, it gorges itself on images. Corporate capitalism at the top filters down as consumer capitalism below, and we monkeys in the middle, scramble for goods and services, sustenance and status. Our greed, our gluttony, our lust, our envy are provoked by apparitions of ideal objects and idealized reflections. American idols abound, and Americans have been induced into idolatry.

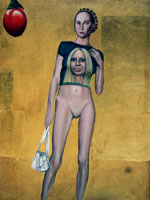

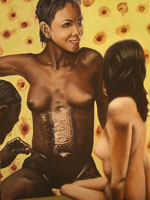

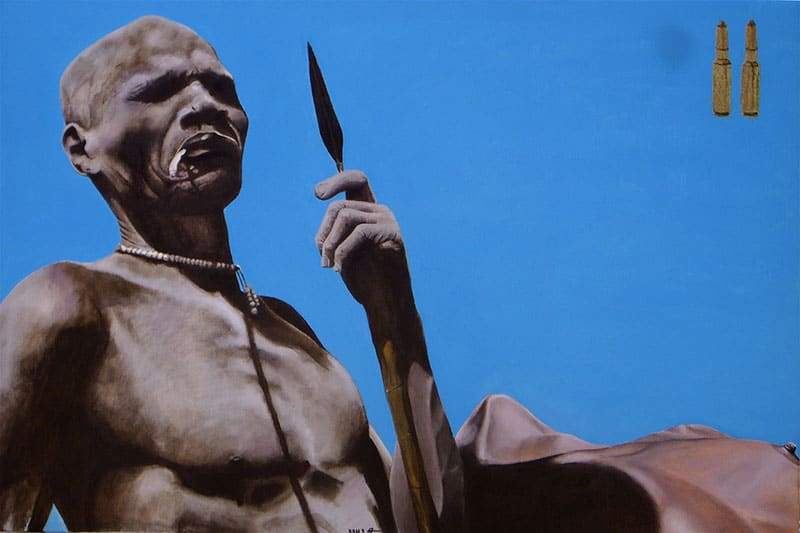

While so many other painters today seek that resonance and durability, either by emulating the manners and even subject matter of their long-dead predecessors or by inventing new manners and seeking new subject matter that might pick up where those predecessors seem to have left off; Haworth casts the achievements of past masters in the corrosive context of present-day visual culture. By clothing people of the past in garb of the present by bringing together the figures of disparate times and places, by superimposing scenes from altarpieces with scenes from television, Haworth piles irony upon irony, constantly bringing our attention back to our relationship with the past - and with the present. Does the nun's embrace of the celebutante tell us that our values are so much more vapid than those of the late-Medieval period, or that that era had its own vapid heroes? Does the late-15th-century prince turn away from the late-20th-century nude in desire or disgust? Do the transformations of western flesh and fame into African models of strength and beauty advocate the nobility of "savagery" or rue its corruption by the pervasiveness of western civilization? And - as the looming minaret reminds us - how do other civilizations respond to that pervasiveness?

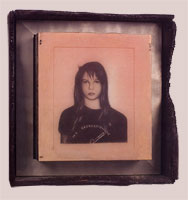

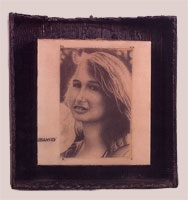

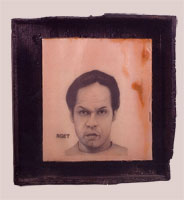

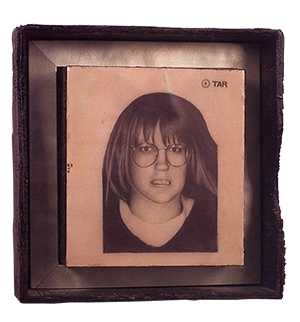

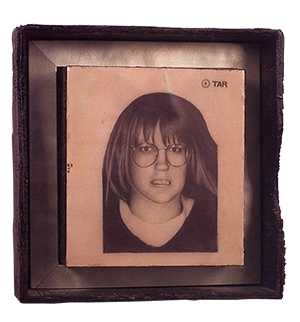

In an earlier body of work, Haworth mused upon the images of those in our society who, for whatever reasons, have disappeared. He drew their visages from the photographs that circulate in our mailboxes and our newsstands, lost again amidst the barrage of imagery and information, and he made sure this encroachment upon their individuality - the consumer babble that encroaches as well upon our own sense of self - registered in his poignant recapitulations. In his newest works, Haworth integrates imagery with information far more thoroughly - with far more jarring results. Unlike the "Lost" series of mixed-media drawings, suffused with sadness and tenderness, these quasi-pop paintings confront and allure us with a wrenching amalgam of anger, hilarity, confusion, and indignation. This, the artist is saying, is not a world that strives for the improvement of the soul, the essential self, but only for the perfection of the body, the public self. Like the views of dirty dishes, half-eaten fruit and human skulls which the Dutch and Spanish still-life painters perfected, Randal Haworth's noisy, miniature-billboard pastiches are mementi more, reminders of our own mortality. Consume all you want blow your whole wad, play the sucker, he cautions: whoever dies with the most toys still dies.

PETER FRANK is art critic for

Angeleno Magazine and the LA

Weekly and is Senior Curator at the

Riverside Art Museum

Artwork By Dr. Haworth

Randal Haworth: Anti-Pop Unrealism

Essay By: Peter FrankAs the American middle class nears the endangered species list, it gorges itself on images. Corporate capitalism at the top filters down as consumer capitalism below, and we monkeys in the middle, scramble for goods and services, sustenance and status. Our greed, our gluttony, our lust, our envy are provoked by apparitions of ideal objects and idealized reflections. American idols abound, and Americans have been induced into idolatry.

Randal Haworth occupies an odd position in this sinned-against-and-sinning society. As a physician, he is expert

in techniques that effectively turn idolaters into the idols they worship, or at least bring them closer. Is

this a capitulation to the economy of consumption, or a means to its transcendence? It is, in any case, an art

form - which is why Haworth practices it. Since childhood he has dedicated himself to the appreciation and

production of art; discouraged from pursuing art as a career, Haworth found an alternate vocation that still

afforded him a hands-on approach to forming images and shaping things aesthetically. As the canard about plastic

surgeons would have it, Dr. Haworth is a Pygmalion for our age.

But, in returning to the making of art itself, Haworth has chosen to make pictures rather than objects. This might seem inimical to his professional practice, which of course deals with solids. but we're wiser to think of his picture-making as complementary. Rather than fashion presences in actual space, Haworth renders his presences in imaginary spaces, in places he determines no less than he does his figures, the better to balance the relationship between figure and ground - and thus control the message.

Haworth's message in effect upends the

consumerist message. It encourages those who view his paintings to regard the visual stimuli around them with a

critical eye. Haworth avers that not only beauty, but wealth, power, and status are only skin deep. He also

suggests that global politics - which hit so close to home of late - are determined by, and in turn determine,

the same psychosocial forces on which consumer capitalism capitalizes. And in the middle of all of this, Haworth

quotes time and again from paintings of the past, from works commonly regarded as milestones along the path of

Western (and occasionally non-Western) art.

Haworth's message in effect upends the

consumerist message. It encourages those who view his paintings to regard the visual stimuli around them with a

critical eye. Haworth avers that not only beauty, but wealth, power, and status are only skin deep. He also

suggests that global politics - which hit so close to home of late - are determined by, and in turn determine,

the same psychosocial forces on which consumer capitalism capitalizes. And in the middle of all of this, Haworth

quotes time and again from paintings of the past, from works commonly regarded as milestones along the path of

Western (and occasionally non-Western) art.

With these quotations Haworth extends to us a two-pronged message. On the one hand (or prong), he serves to provide us cold comfort in the realization that the base motivations driving, diverting, and tormenting us affected our forebears no differently. The Renaissance princess was no less a prisoner of human frailty than is anyone of us. On the other hand, Haworth proffers art itself as a means of looking through, and perhaps getting beyond, the mereness of the human condition. By citing works that stare back at us in museums and art books, that we know at least in passing, or at the very least by type, he points at what he feels is a true kind of persuasive ability, and a true kind of immortality: the beauty of the distinctive image, of the image whose distinction resides in its visual resonance and durability.

But, in returning to the making of art itself, Haworth has chosen to make pictures rather than objects. This might seem inimical to his professional practice, which of course deals with solids. but we're wiser to think of his picture-making as complementary. Rather than fashion presences in actual space, Haworth renders his presences in imaginary spaces, in places he determines no less than he does his figures, the better to balance the relationship between figure and ground - and thus control the message.

Haworth's message in effect upends the

consumerist message. It encourages those who view his paintings to regard the visual stimuli around them with a

critical eye. Haworth avers that not only beauty, but wealth, power, and status are only skin deep. He also

suggests that global politics - which hit so close to home of late - are determined by, and in turn determine,

the same psychosocial forces on which consumer capitalism capitalizes. And in the middle of all of this, Haworth

quotes time and again from paintings of the past, from works commonly regarded as milestones along the path of

Western (and occasionally non-Western) art.

Haworth's message in effect upends the

consumerist message. It encourages those who view his paintings to regard the visual stimuli around them with a

critical eye. Haworth avers that not only beauty, but wealth, power, and status are only skin deep. He also

suggests that global politics - which hit so close to home of late - are determined by, and in turn determine,

the same psychosocial forces on which consumer capitalism capitalizes. And in the middle of all of this, Haworth

quotes time and again from paintings of the past, from works commonly regarded as milestones along the path of

Western (and occasionally non-Western) art.

With these quotations Haworth extends to us a two-pronged message. On the one hand (or prong), he serves to provide us cold comfort in the realization that the base motivations driving, diverting, and tormenting us affected our forebears no differently. The Renaissance princess was no less a prisoner of human frailty than is anyone of us. On the other hand, Haworth proffers art itself as a means of looking through, and perhaps getting beyond, the mereness of the human condition. By citing works that stare back at us in museums and art books, that we know at least in passing, or at the very least by type, he points at what he feels is a true kind of persuasive ability, and a true kind of immortality: the beauty of the distinctive image, of the image whose distinction resides in its visual resonance and durability.

While so many other painters today seek that resonance and durability, either by emulating the manners and even subject matter of their long-dead predecessors or by inventing new manners and seeking new subject matter that might pick up where those predecessors seem to have left off; Haworth casts the achievements of past masters in the corrosive context of present-day visual culture. By clothing people of the past in garb of the present by bringing together the figures of disparate times and places, by superimposing scenes from altarpieces with scenes from television, Haworth piles irony upon irony, constantly bringing our attention back to our relationship with the past - and with the present. Does the nun's embrace of the celebutante tell us that our values are so much more vapid than those of the late-Medieval period, or that that era had its own vapid heroes? Does the late-15th-century prince turn away from the late-20th-century nude in desire or disgust? Do the transformations of western flesh and fame into African models of strength and beauty advocate the nobility of "savagery" or rue its corruption by the pervasiveness of western civilization? And - as the looming minaret reminds us - how do other civilizations respond to that pervasiveness?

In an earlier body of work, Haworth mused upon the images of those in our society who, for whatever reasons, have disappeared. He drew their visages from the photographs that circulate in our mailboxes and our newsstands, lost again amidst the barrage of imagery and information, and he made sure this encroachment upon their individuality - the consumer babble that encroaches as well upon our own sense of self - registered in his poignant recapitulations. In his newest works, Haworth integrates imagery with information far more thoroughly - with far more jarring results. Unlike the "Lost" series of mixed-media drawings, suffused with sadness and tenderness, these quasi-pop paintings confront and allure us with a wrenching amalgam of anger, hilarity, confusion, and indignation. This, the artist is saying, is not a world that strives for the improvement of the soul, the essential self, but only for the perfection of the body, the public self. Like the views of dirty dishes, half-eaten fruit and human skulls which the Dutch and Spanish still-life painters perfected, Randal Haworth's noisy, miniature-billboard pastiches are mementi more, reminders of our own mortality. Consume all you want blow your whole wad, play the sucker, he cautions: whoever dies with the most toys still dies.

PETER FRANK is art critic for

Angeleno Magazine and the LA

Weekly and is Senior Curator at the

Riverside Art Museum